Fishing

Bute Inlet and the deep channels that surround Stuart Island are influenced by extreme tidal currents that bring cold, nutrient-rich water from the depths and constantly recirculate it keeping the water temperature at a cool 10c year round.

These sea conditions produce a photosynthesis-based richness that affects the entire food chain. From phytoplankton and krill, to herring and anchovy, to salmon and cod, seals and sealion, dolphin and whales right to the top predator, the Orca. All of these native species are brought together, benefit from, and contribute to the richness of the area.

We see all 5 species of Pacific salmon in these waters: Chinook, Coho, Pink, Chum and Sockeye.

The most sought-after is the Chinook Salmon. The largest of the 5 species, it is world-reknowned for its size, strength and majesty. Recent conservation efforts to protect "at-risk" Chinook stocks has determined selective, geographic areas of retention and non-retention. (see "fishing regulations")

Gernerally, we have two distinct periods to our season. Late spring/early summer is when immature Chinook, called "feeders", are most prolific and caught primarily in Bute and Toba Inlets and surrounding Discovery Islands. Reaching 30+ lbs, these fish are actively feeding and particularly robust.

As the summer peaks, the following two months (July thru August) is when mature Chinook migrate through the area. Fishing locations change to areas that branch off from Johnston Straits and Nodales and Cordero Channel. Locally caught Chinook have tipped the scales at 72 lbs, and Tyee-class Chinook are caught weekly during this peak season.

Coho Salmon migrate through these waters during the late summer Aug - Sept. These chrome aerial-fighters can top the scales at 20 lbs. and provide a sassy, seasonal alternative to Chinook. Recent openings in sections of Area 13 (Bute Inlet), have allowed seasonal retention opportunity of both wild and hatchery Coho. (See "fishing regulations")

The method-of-choice when fishing for salmon is trolling. Vast areas with strong currents means fish are constantly on the move as they forage and migrate. Trolling with downrriggers allows you to fish at accurate depths and cover large areas as you search for your quarry.

The dramatic relief between mountains and sea allow for a near-shore fishery where, at times, your rod tip almost touches the rocky shoreline. In the early season, we typically fish between 70-100 ft and rarely deeper than 120’. Fighting a Chinook salmon at these relatively shallow depths is challenging. Different from a surface battle and hardly comparable to catching at depths beyond 200’, these fish have room to move. Twisting and turning, running and sounding it’s hard to deny the extraordinary power and vitality of this remarkable species.

Bottom Fishing

Bottom Fishing

Bottom fishing is a good compliment to a day of salmon fishing. There are several species to be targeted with preference for Ling Cod and Rockfish. Ling cod are voracious, aggressive fish and are often caught trying to eat a smaller fish already on the hook. Rockfish grow and mature very slowly so stock regeneration is lengthy. Conservation efforts and modest retention limits exist for both species.

The beauty and majesty of BC’s south-coast, mainland inlets and the deep channels and passages that weave their way around the Discovery Islands is unparalleled. Steep geography and unimaginably deep water offer a dramatic seascape and stunning views as the Coast Mountains, quite literally, rise out of the ocean.

Stuart Island is nestled at the entrance to Bute Inlet about 31 nautical miles Northeast of Campbell River, BC. It serves as a hub for the area in terms of resort locations, community services and boating traffic. From here, there is easy access to a vast area and numerous fishing locations:

Remote, but easily reachable by boat or floatplane, these protected waterways offer something that many fishing locations do not: calm sea conditions.

Comfort, while on the water, is a luxury that anyone can appreciate. More days than not, the water is smooth-as-glass and devoid of swell with just a breath of thermal wind to cool. And the unique geography always offers a choice of refuge from any wind.

However, what this area offers goes much further; beyond physical beauty, picturesque views and comfortable water conditions. It is a phenomenon that makes this area incredibly unique and has influenced many a guest to visit, stay and return; including myself! Deep channels and inlets linked by shallow, narrow passages and influenced by extreme tidal conditions, together, produce conditions rarely found elsewhere… tidal rapids!

Read more

Over the years, fishing regulations for Chinook salmon have become increasingly restrictive with daily size and catch limits being systematically reduced. More recently, several runs of Chinook originating from the Fraser River and its tributaries are experiencing record-low returns and efforts are being made to conserve these “at-risk” stocks. As such, since 2019, tidal water fishing regulations for Chinook salmon on the south coast of BC have taken a hard turn.

These new regulations have imposed, for the first time, a maximum size limit and substantial non-retention periods to allow more of these migrating, “at-risk” Chinook salmon to return to their rivers of origin to spawn and replenish stocks.

And so, as certain Chinook populations approach dangerously low levels, recreational salmon fishing is being redefined where conservation and stewardship are key themes. Achieving a critical balance between sustainable, selective harvesting and conservation has become a priority.

Citizen science

I recall some 15 years ago, guides in the Stuart Island area were approached by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) to help them with data collection for the Chinook salmon fishery. Log books were given out to participating guides, to be updated throughout the season and collected by DFO in the fall.

Unfortunately, due to DFO staff and budget constraints, the data was not analyzed nor summarized in any timely manner. Frustrated with a lack of feedback or results, I lost interest in the program after about 5 years of participation.

Fast forward to 2017, when the logbook/data collection program was re-vitalized and named the “Avid Angler Program: Local expertise in fishery science” (AA).

I was, of course, skeptical considering my last experience but encouraged upon hearing that the Sport Fishing Institute (SFI) was involved in administering the program and ensuring the results were made available to AA participants in a timely manner.

The new program is more rigorous and requires tissue samples to be taken to sequence the DNA and determine river origin. Add to this the Chinook non-retention period, and we are faced with significant tasks associated with increased handling time to capture all the required data.

Catch and release is not foreign to us. For years, we have had a non-retention regulation on Coho Salmon in area 13. So, we are adept at methods of in-water, catch-and-release that, in our opinion, does not cause significant harm. However, in order to obtain data for the new program we needed to net these fish and bring them aboard for a period of time before releasing them.

Our local fishery advocate, Rupert Gale, with support from the Ritchie Foundation, came up with the idea of a fish cradle. A collapsible trough that fit on the swim grid which we could fill with saltwater and serve as a holding tank while we conducted our citizen science.

Our local fishery advocate, Rupert Gale, with support from the Ritchie Foundation, came up with the idea of a fish cradle. A collapsible trough that fit on the swim grid which we could fill with saltwater and serve as a holding tank while we conducted our citizen science.

It was a success! After a trial period, it became immediately apparent that immersing the fish in saltwater, onboard, after capture was an ideal method to safely and reliably gather the required data.

And, of course, this whole process unfolds in front of my guests who are eagerly peering over the transom to get a closer look at their catch and to help me with measurement and sampling. Once the science is complete, a photo is taken of my guest with their fish just before it is slipped back into the sea. Watching the salmon swim away, there is always a collective, "Ahhh...!" moment. Complete satisfaction with the entire process of fishing, hooking, landing, measuring, sampling and releasing has been indisputable. It was then I realized how interesting and captivating the process can be.

And, of course, this whole process unfolds in front of my guests who are eagerly peering over the transom to get a closer look at their catch and to help me with measurement and sampling. Once the science is complete, a photo is taken of my guest with their fish just before it is slipped back into the sea. Watching the salmon swim away, there is always a collective, "Ahhh...!" moment. Complete satisfaction with the entire process of fishing, hooking, landing, measuring, sampling and releasing has been indisputable. It was then I realized how interesting and captivating the process can be.

With SFI "leading" the program, data is collected and analyzed and by year’s-end we have some preliminary results. For example, a 2020 creel summary showed 68 AA participants on the South Coast had caught and sampled 3368 Chinook. Individual contributions revealed that, surpisingly, I was in the top 5 south coast contributors. Later that spring the data had been fully analyzed and we had a timely, comprehensive view of the previous season’s kept and released Chinook data.

Results

Results

When DFO imposed the non-retention periods for Chinook salmon in the late spring of 2019 they came under immense criticism. I was among many members of our coastal communities that depended on this natural resource and saw my livelihood threatened. Aside from voicing my concerns to local government, I felt like a spectator with little control of my future in this respect.

However, it became evident that conservation of Chinook stocks is something we can do, collectively, to support their survival and, consequently, the survival of the recreational fishery. Sustainability may only be achieved by striking a balance between selective harvesting and conservation. I have learned that science is the driving force behind decisions on regulations and in the absence of adequate scientific data you are at the mercy of broader speculation amidst an abundance of caution.

By mid-June 2020, DFO announced the first geographic exception of select mainland inlets where limited Chinook retention would be permitted for a 2 week period ahead of the July 15 opening for the majority of the south coast. These sub-areas included portions of Bute and Toba Inlet: 13-19, 13-20, and portions of 15-5 (see Area 13 Map, Area 15 Map).

In my recollection, this was the first concession ever offered by DFO. So, how did this come about? For those of us who fish the mainland inlet waters near the Discovery Islands we know from experience the absence of mature, migrating Chinook at this time of year. But we had not proved it yet with science. On a political front, the Sport Fishing Advisory Board (SFAB) was providing a strong voice for recreational fishers on a federal level to get DFO to consider selective harvest options.

Not surprisingly, data from the AA program revealed the river origins of the sampled Chinook and it was determined that, in these particular mainland inlet waters, the likelihood of encountering at-risk, Fraser River Chinook was extremely low. This year 2022, the mainland inlet opening begins April 1; a full 3.5 months ahead of the general opening of July 15. (see "fishing regulations" for further information)

I have since become a strong advocate of citizen science and the Avid Angler Program. And not simply because it supported a selective fishery in my area. Fundamentally, it acknowledges the vast wealth of firsthand knowledge accumulated by those of us who spend so much time fishing. This hands-on knowledge can be gathered, organized and quantified to become fact instead of conjecture. As such, it allows me to be involved in a critical part of the scientific process that directly affects the regulations that govern the fishery of which I am a part.

I am no longer a spectator but a participant.

UBC Research Study

UBC Research Study

In the spring of 2021, I had an opportunity to participate in a research study from the UBC Pacific Salmon Ecology and Conservation Laboratory. Post-graduate Stephen Johnson was conducting research for his doctoral thesis entitled: Reel Survival: Using acoustic telemetry to investigate recreational fisheries post-release survival of Chinook and Coho salmon

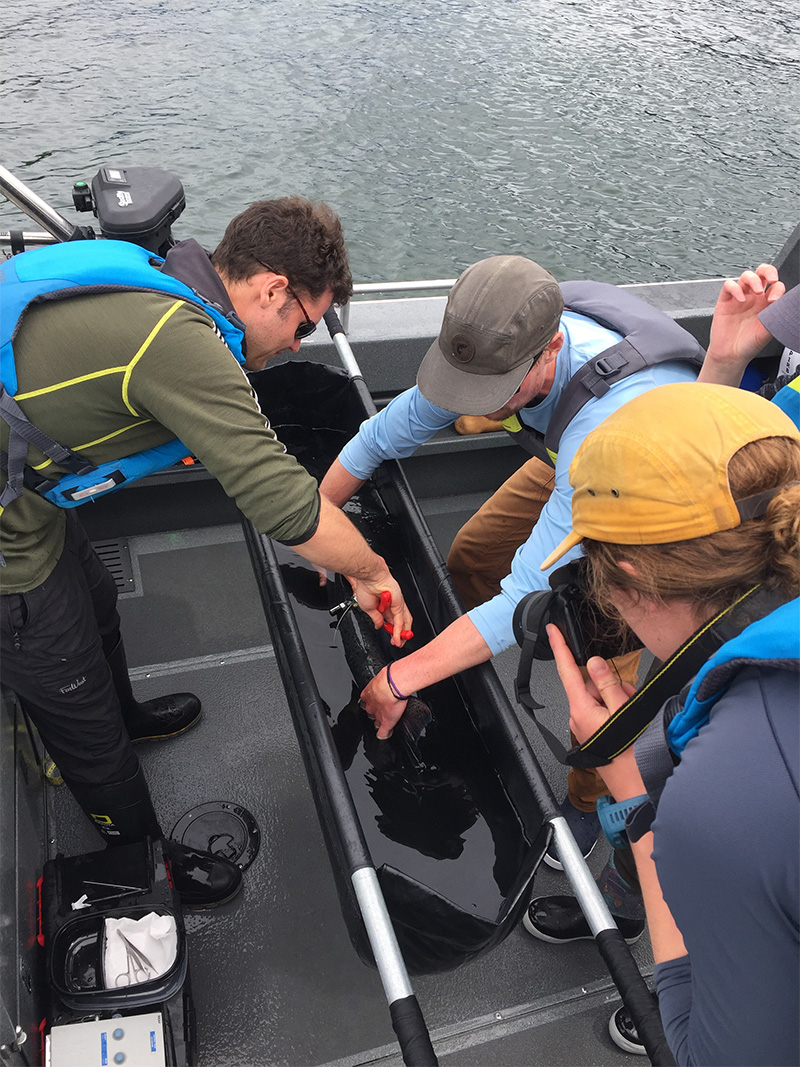

The goal was to observe, test and tag approximately 180 sport-caught Chinook salmon in a 2 week time frame in the Toba Inlet/Discovery Islands area. I was among 3 local fishing guides who assisted in this effort. Stephen and his 3 associates operated from a “mothership”, where all of the scientific testing, sampling and observations were made.

Once we hooked and landed a suitable-sized Chinook, we would signal the mothership and they would retrieve the fish from us while it remained in the net and in the water.

Once we hooked and landed a suitable-sized Chinook, we would signal the mothership and they would retrieve the fish from us while it remained in the net and in the water.

On the mothership, in addition to location data and DNA sampling, they would record observations of the fish’s health. From pre-existing conditions (i.e. evidence of disease or previous injury), to injury caused during their capture (i.e. by gear type and hook size, hook location and by netting), to overall observations of fight time, air exposure and blood loss.

After recording observations, they would attach a physical acoustic tag for identification and tracking before releasing the fish.

Through placement of stationary underwater receivers in different locations in the upper Georgia Strait and Discovery Islands, tagged fish that survived could be identified and their movement tracked over the next 18 months.

“Kintama”, an animator computer program, provides an accurate visual representation of the movement of all the Chinook which were tagged in the Discovery Islands in the spring of 2020. Using data collected from the receivers, each released Chinook can be individually traced for up to 18 months and provides much more insight as to their extended survival and range of movement.

“Kintama”, an animator computer program, provides an accurate visual representation of the movement of all the Chinook which were tagged in the Discovery Islands in the spring of 2020. Using data collected from the receivers, each released Chinook can be individually traced for up to 18 months and provides much more insight as to their extended survival and range of movement.

(*By choosing “Discovery Islands Chinook RU” from the Case menu in the Kintama program and using the zoom function to focus the map, one can visually track fish movement by stock composition.)

Findings

This study is still in progress so principal findings are not yet available. However, there are some preliminary results that, although not necessarily conclusive, do prove interesting.

DNA sequencing of all Chinook salmon caught in the Discovery Islands that spring identified two dominant populations coming from East Vancouver Island rivers: The Puntledge River and Qualicum River. This finding supported our collective experience and the Avid Angler program data confirming the relative absence of at-risk Fraser River Chinook.

I recall an example that left me slack-jawed in amazement. One particular caught Chinook showed evidence of significant damage from being hooked once before. Further observations determined its health to be poor and it was considered a certain mortality. Surprisingly, ten days later it was identified by a receiver in the Northern Georgia Strait. Six weeks later, photo evidence revealed it was recaptured a third time by a recreational fisher and released. And 147 days later it was recovered in the Little Qualicum River hatchery with the acoustic tag still intact. This incredible example of survival not only showcases the efficacy of acoustic telemetry but is a true testament to the utter resilience of the species!

There were a significant number of hatchery Chinook identified by their missing adipose fin; about 11%. However, using PBT (Parental Based Tagging), which genetically identifies hatchery fish through brood stock DNA, the number of hatchery fish encountered that spring climbed to a whopping 47%!

This finding is very significant for the Mark Selective Fishery (MSF) being advocated by the Sport Fishing Advisory Board (SFAB). If visual marking (fin clipping) was more pervasive for hatchery-raised chinook, there could be a possibility of a MSF; an added opportunity for recreational fishers to retain a marked, hatchery Chinook during a non-retention period for wild Chinook.

The significance of this catch-and-release mortality study is many-fold and perhaps, more importantly, could be a springboard for future initiatives. Stephen Johnson speaks of a “best practices” hand book for recreational fishers that would outline equipment suggestions and release and handling techniques that could minimize the injury and mortality of caught and released fish.

Together with citizen science, constructive initiatives like these are part of the future of conservation, selective harvesting and the strive for sustainability in our recreational fishery for current and future generations.